I’ve always felt a strong connection to Paul Theroux, due largely to our shared legacy as Peace Corps Volunteers in Malawi. When I expressed reluctance about taking an assignment teaching English there in the 90s, the recruiter suggested I read My Secret History, part of which was inspired by Theroux’s experience as an English teacher in Malawi in the 60s. I found the book funny, intelligent, irreverent, and most importantly: exotic. So off I went to Malawi.

It’s two decades later, and while I claim no personal connection to him, Theroux’s become a fixture in my household. He’s part of the long-running repartee shared by husbands and wives over the course of a marriage. I enjoy Paul Theroux, and his work figures prominently in my growth as a writer. My wife, on the other hand, thinks him a toad.

This is relevant. Deepa also served as a Volunteer in Malawi, swearing in with me and 37 others on December 6th, 1996 (an easy date to remember: the day before Pearl Harbor Day). As is usual with this ceremony, the U.S. Ambassador led us in the oath of service. He arrived early for some unrelated ribbon-cutting event, and joked during his remarks that his wife was going to be furious with him because he’d forgotten to send the driver back for her. When she finally arrived, she was in the company of a rough-looking white man in a polo shirt and hiking boots, haggard visitor who looked more like a workman than the companion of the top U.S. envoy. Naturally, we assumed he was the driver. Why, we wondered, should the Ambassador require this obvious non-local to drive him around a country full of jobless people?

We soon forgot the strange azungu and turned our attention to the remarks being made in the local language by the strongest Chichewa speaker in our group, an honored role and a great Peace Corps tradition that demonstrates respect for the country of service. The new home. With the ceremony over, we sought out punch to celebrate our status as Volunteers. The white stranger, for his part, had this off-hand comment for the young woman who’d worked so hard on her remarks: “Nice speech. But you should have used some proverbs. Like…” blah, blah, blah.

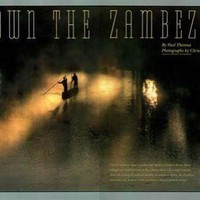

Typical Theroux. Always the smart guy. Always the critic. He’d returned to Africa to write a story about a boat trip along the Zambezi for National Geographic, and took the opportunity to visit the country that had expelled him in 1965 (he’d been declared Persona non-Grata for allegedly supporting a coup against then-President for Life Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda). For this Volunteer (who many years later became my wife) his manner of observation turned out to be just as arrogant and intolerable—The show-off! The pompous, patronizing know-it-all!—in person as she later found him to be in print.

That is Theroux’s reception, in my home and afield: revered, reviled. It’s a pleasure to ring in the new year reading Mr. Bones, enjoying all the things that make his work wonderful. And horrible.