I intended just to share Peter Tomsen’s three-year effort in Beijing to convince Chinese government conservatives to invite a Peace Corps program into the country. To do it right, I had to underscore how and where Tomsen developed the cultural intuition he would rely on to get the job done.

Through full communication—two-way cultural and linguistic transmission—we built sincerity and trust... That two-way cross-cultural communication developed in the Peace Corps contributed to my interpersonal relations with Chinese officials during seven years in China.

-Peter Tomsen

He wasn’t alone in this. Indeed, the example of how his intuition proved critical to success is reinforced by the fact that his co-negotiator, Korea RPCV Jon Keeton, recognized and deployed the same tactic: speaking to another culture from within that culture’s envelope.

Competent practitioners enter a mindset wherein they no longer translate the local culture. They become the culture, are inside it looking out. The practitioner is like a fish in water.

This sensation emerges in Peter Tomsen’s story. He forges an intercultural understanding in Nepal and brings it to bear two decades later in China. There he concludes the central agreement to establish the first Peace Corps program in a communist country, the culmination of a decade of planning and dreaming and batting away the realities flying in the face of such a thing ever occurring.

Nepal III

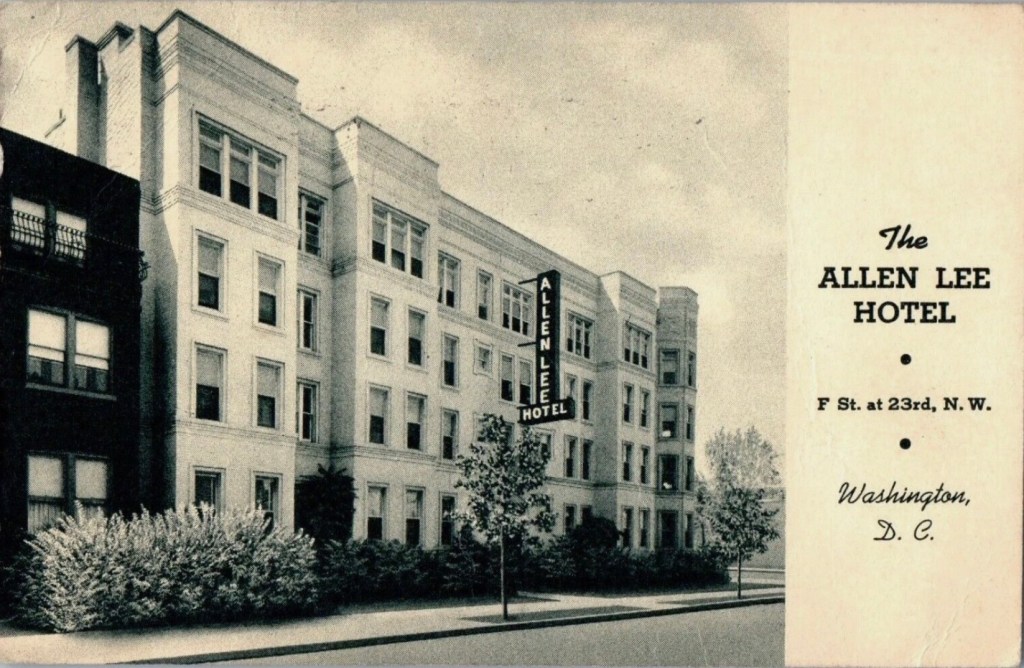

On a bright day in February 1964, Peter Tomsen checked into the Allen Lee Hotel near the George Washington University campus. There Nepal III convened thirty-seven trainees, including another future U.S. Ambassador, Victor Tomseth.

Under intense classroom pressure they buckled down for three months of language and South Asia area studies. After hours, they sat on hotel balconies with guitars, singing popular folk songs, especially Joan Baez and Judy Collins.

Follow-up training on Hawaii’s main island included mountain trekking, roughing it, and teaching students in Hilo classrooms.

Peace Corps assigned Tomsen and two others to Pokhara, a valley below western Nepal’s high Himalayas. They had a cardboard locker filled with hundreds of books, sturdy Kelti backpacks for rugged mountain trekking, household kits with sleeping bag, canteen, and pressure cooker. Their small medicine chest included bandages, syringes, tetracycline, malaria tablets, Lomotil for the GI, Halazone to purify water.

They built their own charpi (latrine) and made round-the-clock visits. On the mud-baked chulo (stove) they prepared daal bhat tarkari (lentils, rice, veggies) for dinner before unrolling their sleeping bags over thin mattresses. They read and chatted by lantern before sleep, waking at sunrise as the bazaar outside came to life.

Tomsen taught political science, civics, and comparative governments at Prithvi Narayan College a hundred yards across a field from his house. Each morning he looked up at the Himalayan range forty miles off, Annapurna, Dhaulagiri, and Machapuchare white-capped all year round.

He became a frequent dinner guest at the campus home of history teacher Mahendra Singh Thapa, visiting his family for Indian card games and long conversations. Thapa asked Tomsen to join him teaching English at his private night school. They followed their flashlight beams across rice paddy dikes and fields, walking two hours through wind and rain, some nights returning past ten. They became like family.

Few Nepalis spoke English, motivating Tomsen to learn Nepali. Students dropped by to play chess, casual interactions that deepened his cultural perception. He drank tea with fellow teachers, their conversations turning from professional affairs to family and tradition.

He chattered with the woodcutter and the porters plying the hills with eighty-pound baskets. Complete strangers on mountain treks, encountering this foreigner, burst into song, and Tomsen responded in kind.

Tibetan Refugee Camp

On weekends he trekked up to the open-air school of a Tibetan refugee camp, the students sitting on the ground by the blackboard. Tomsen taught basics: letters and words. Given the distance, he occasionally overnighted, got to know the culture, and developed a rudimentary knowledge of Tibetan.

Invited one night to a thatch and bamboo house, Tomsen found a sick elder laid out under a dark cloak. A witch doctor, clad in black with a high, angled hat, danced around the bed, chanting for hours, shaking a dorje (lightning symbol) and ringing a bell to drive out the evil spirit.

The darkness, the dance, the chant, the amulets shaken to expunge disease, all transported Tomsen to a different millennium. Same was true at late-night drukpa dances, with men, women, and children swaying in a large circle around a fire, singing Tibetan songs and laughing under the full moon.

Tomsen extended his service to help establish vocational training in the camp. He labored alongside workers assigned by the Tibetan chiefs to build a one-room hut for himself. He urged the chiefs to allow a quarter acre plot to demonstrate gardening.

As sheep and yak herders going back generations, more adapted to plying the vast Tibetan plateau than tilling the land, the chiefs doubted the purpose. He persisted, the force of his sincerity winning them over.

On a return visit two years later, Tomsen saw a flourishing school, witnessed gardens around every home, beans, squash, corn, and cucumber coming up thick. Two years earlier, these yak and sheep herders wouldn’t have dreamed of a sedentary practice like farming.

In Good Time

As a former Peace Corps Volunteer, the opportunity to contribute to the entry of the Peace Corps into China was a high point during my second China assignment.

From 1986-1989 Ambassador Winston Lord entrusted Tomsen, his deputy at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, with negotiating the entry of Peace Corps Volunteers into China. As Tomsen saw it, the key would be to influence his negotiating counterpart, Assistant Foreign Minister Liu Huaqiu, to support the initiative.

He needed such an ally to sway the Politburo, which would make the final decision. Politburo conservatives, holdovers from the Mao era, and Chinese intelligence agencies proved major obstacles after years of propaganda vilifying Peace Corps Volunteers as CIA.

Tomsen and Lord believed that pro-reform members of the Chinese Communist Party and the Deng Xiaoping government would see the utility. After all, Deng’s four modernizations included opening up to the outside world. English being the mainstream international language, China would remain isolated as long as its citizens didn’t speak English.

In 1986 Peace Corps Director Lorette Ruppe visited China to lay the groundwork for a program. On the sidelines, Tomsen and a team of embassy RPCV FSOs concluded that the best strategy would be a patient approach, letting the issue wind its way up the Chinese bureaucracy. “In good time” became the mantra.

Personalized Approach

Tomsen raised the issue with favorably disposed officials like Assistant Minister Liu. He personalized the approach, describing his experience as a volunteer. He shared Peace Corps literature about successful English programs in the region and put these insights in the Chinese context.

The deliberate method paid off: in March 1988, Chinese Foreign Minister Wu Xueqian told a Washington Press Club audience China agreed in principle to the program and the real work began.

Tomsen’s U.S. co-negotiators exhibited the same empathetic nature as Tomsen. Jon Keeton, an RPCV and former Korea Peace Corps Country Director, did most of the talking. A skilled cross-cultural communicator like Tomsen, he also knew how to reach the Chinese.

As China RPCV Daniel Schoolenberg points out in his excellent account: “The turning point came when Keeton figured out how to communicate on their terms.”

He urged them to recognize that American “Friends of China,” the offspring of missionaries and others who’d spent long periods in China decades earlier, were getting old. They were passing on. China needed a new cadre of Americans to see the country in its true light, to understand and love China, to go on to become diplomats and scholars.

As the interpreter translated Keeton watched the expressions of the Chinese officials begin to change. They were now looking at him with new interest.

-Daniel Schoolenberg

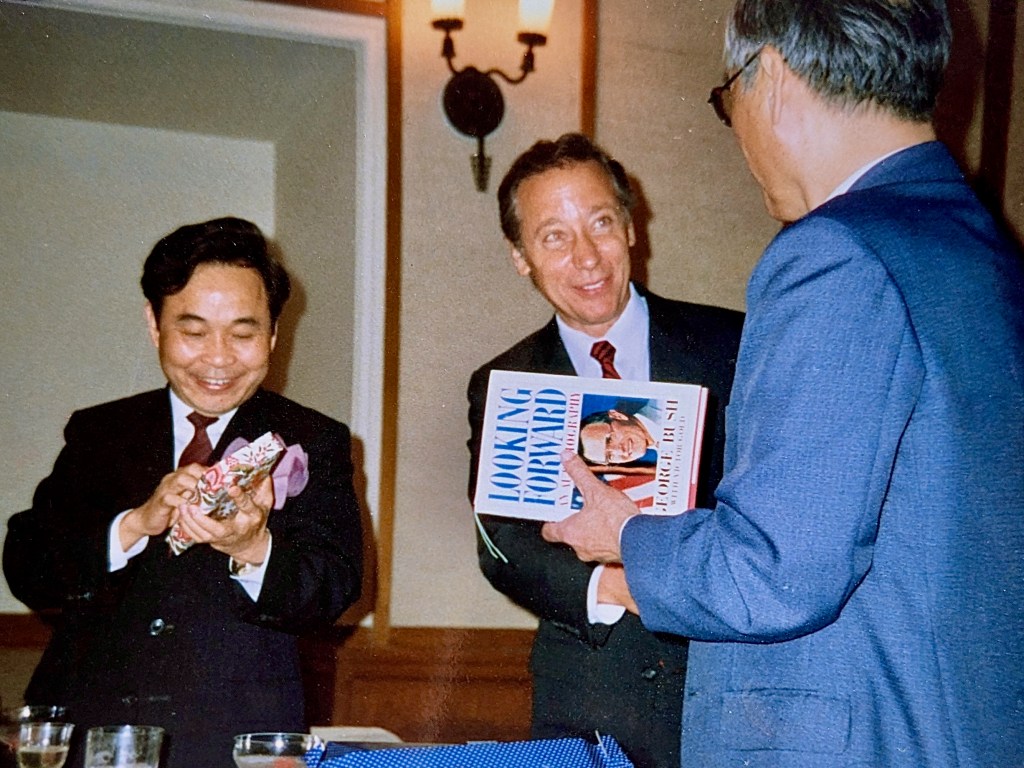

Three rounds of talks through 1988 brought Keeton to the point of visiting potential host schools and training sites in December. Assistant Minister Liu hosted a welcome banquet that preceded the final talks. All agreed that volunteers must be U.S. citizens friendly to China with adequate degrees, including training on teaching EFL. China would provide free housing and teaching facilities, Peace Corps the monthly allowance, and classroom materials would be chosen by mutual consent.

The U.S.-China Friendship Volunteers

The agreement was formalized through an Exchange of Letters between Ambassador Lord and the Chinese Secretary General for International Exchanges Ge Shouqin in April 1989. It called for twenty volunteers in China One, teaching English in three teacher training colleges, two medical colleges, and an animal husbandry institution in Western China. Chinese propaganda having spoiled the Peace Corps’ name, they would be called the U.S.-China Friendship Volunteers at the suggestion of Assistant Minister Liu.

The Peace Corps planned to have volunteers in China by the end of August. Given the inevitable scrutiny of this first group, they set about hand-picking the best of the best. Through a week-long process of in-person evaluation in West Virginia, they selected twenty-three to begin training at American University in May.

This proved a busy time for Tomsen, his last three months in China that included historic events: a three-day visit by President Bush in February; the student mobilization on April 22 sparked by the government-organized funeral of purged reformer Hu Yaobang; Soviet leader Gorbachev’s May 15-19 summit with Deng Xiaoping; the Chinese Communist Party’s imposition of martial law on May 20; and, finally, the June 3-4 Tiananmen massacre.

Tomsen also served as Acting Chief of Mission, Ambassador Lord having departed soon after the April 5 formal Exchange of Letters. His replacement, James Lilley, wouldn’t arrive until early May.

By the morning of May 15, a million or more demonstrators filled the Square and its periphery, forcing the government to cancel the ceremonial welcome for Gorbachev there. Even at this heady moment, even despite the major convulsions surrounding their imminent departure, Tomsen and his wife, Kim, made time to commemorate the deep friendships they’d forged at the official level.

Assistant Minister Liu, Tomsen’s closest problem-solving partner and good friend, with whom he’d spent hundreds of hours collaborating on thorny issues, invited the couple to a second farewell dinner on May 16.

In his stand-up welcome toast, amid much laughter, Liu proclaimed that the evening’s meal featured Texas steaks, just as merrily noting the same steaks would be served to the Soviet delegation in the adjoining villa. The Tomsens departed four days later, the day the CCP declared martial law.

Back on U.S. soil, Tomsen met with the would-be volunteers of China One soon after the massacre, sharing his view that it was unlikely their program could proceed. By June 23rd, the Chinese—not the U.S.—made the decision to postpone China One, and those trainees were sent elsewhere.

Secret trips in July and December by National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft and his deputy Lawrence Eagleburger sought a reversal of China’s decision, to no avail. The issue persisted in top-level meetings between American and Chinese officials for the rest of Bush’s term, but the first group of U.S.-China Friendship Volunteers wouldn’t arrive until the Clinton Administration in 1993.

By then Tomsen had completed his tour as Special Envoy to the Afghan Resistance and was serving as Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs. Two years later, he would set out for Armenia as ambassador.

Read more from Tomsen’s oral histories with the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training:

ADST Oral History 1 – Peace Corps and Vietnam

ADST Oral History 2 – China negotiations and Tiananmen Square

##

Leave a comment