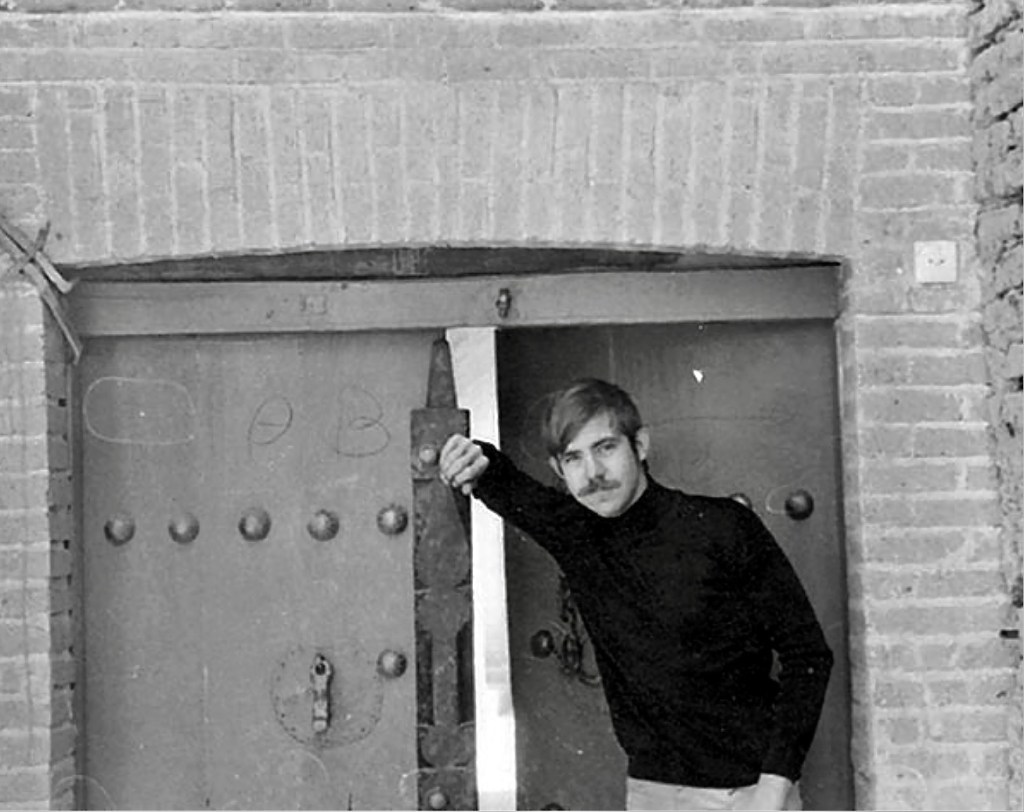

Michael Metrinko served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Turkey from 1968-70 and Iran 1970-73. This first of two sketches about him precedes a final sketch covering crisis survival in Tehran from 1979-81, where Metrinko was one of four RPCV hostages held during the U.S. Embassy siege. The full profile is scheduled for publication in Profiles in Service in 2026.

Five years at the edge

Metrinko’s Peace Corps group landed in Ankara in the summer of ‘68, a dust storm stirring an apocalyptic haze around the World War I-era Dogpatch airfield. Peace Corps staff transferred them to a dorm at the University of Ankara and said, “Drop your bags and freshen up. The director wants to talk to you in thirty minutes.”

They assembled in a snack bar, tired and wary. The director entered and welcomed them to Turkey. “A challenging country, a wonderful place. Before I say anything more, come take a piece of paper from this bowl. It’s a surprise for everyone.”

Told by the director to open the paper, Metrinko saw a strange word there.

“Every piece has the name of a town in Turkey. Go there. Come back in a week and prove you’ve been there. This dormitory is now closed. Goodbye.”

This frightened a few, dispirited others, but lit a fire in Metrinko’s chest. An adventure was just the thing he’d come for. In a tattered guidebook his town rated one line: “A typical Anatolian wood town, population 1,200, on the road from Ankara to the Black Sea.”

A map showed he could pass right through it and continue up to the sea for the week.

Two others had the same idea and off they went. The bus blew past Metrinko’s town and the trio dropped at Ereğli in the late afternoon, a harsh, coal-shipping port, not a beach resort. The exhausted travelers rented all five beds in a hostel, Metrinko, future FSO Stan Bigelow, and a young woman.

Scouting for a meal, Metrinko and Bigelow found themselves invited to a mountaintop village an hour away, the wedding of a Turkish army sergeant. Transvestite performers entertained hundreds of people, all drinking, the place reeking of hashish, their heads on pillows beside strangers the next morning and no transportation back, their money nearly gone.

In survival mode, they opened up, engaged strangers, made fast friends. When, finally, they made it back to Ankara a week later, they possessed much more than a souvenir collected from a random town. They’d absorbed words and phrases, the names and tastes of foods and beverages, seen ancient things built by the Romans and the Greeks, and learned how to engage a new society fearlessly, within its limits and according to its rules.

The firehose treatment taught Metrinko survival on a primal level, meeting new people, getting comfortable staying in their homes. Cultural adjustment came quickly after that.

For two years he taught university English in Ankara, befriending students and faculty, learning from them as much as he taught, traveling widely to learn the country. After a filler job interpreting for an American archaeologist on the Black Sea, he transferred to a Peace Corps job in Iran.

His first year teaching young boys in Sonqor was a struggle. A four-hour bus ride from anywhere, the conservative outpost of 9,000 residents sat on a wide plateau surrounded by impenetrable mountains, isolation preserving the town’s Turkic identity. Nearby village Kurds and the local Turks all struggled to speak Persian, the country’s official language. Everyone, Metrinko included, spoke a trilingual mélange of Kurdish, Turkish, and Persian.

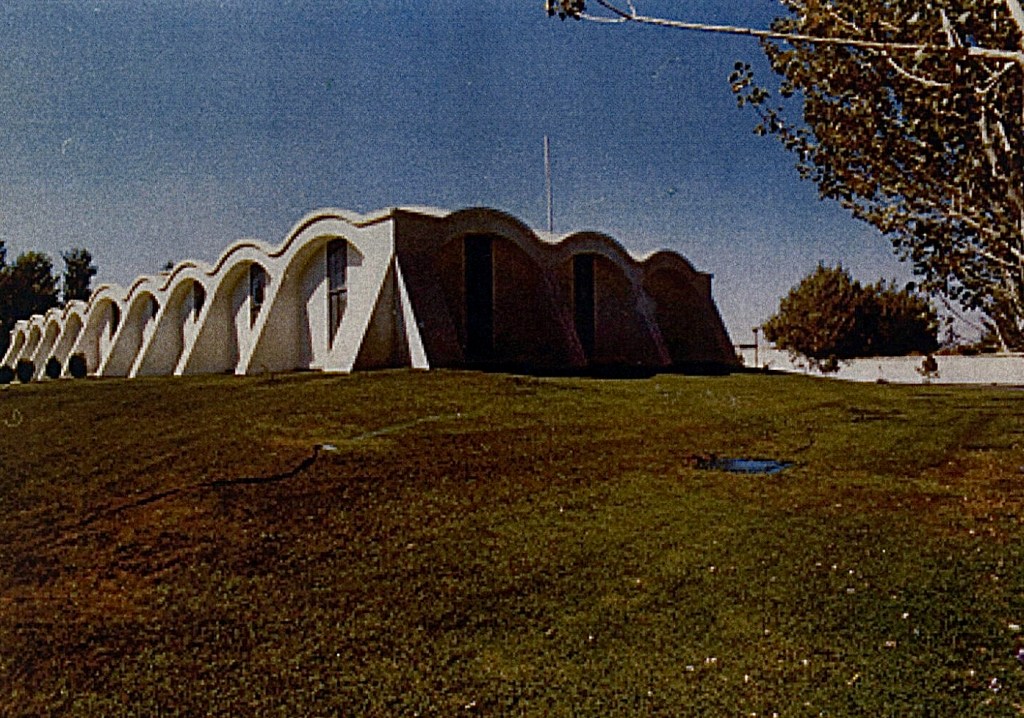

He transferred the following year to a teacher training college outside Tehran, a beautiful co-ed campus in Mamezan, teaching an elite group of teachers who’d completed service in Iran’s Literacy Corps—a substitute for their two-year mandatory military service. He stayed two more years, taking the Foreign Service exam at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, absorbing the country, making lifelong friends and contacts.

After five years in Turkey and Iran, the Foreign Service inducted him and turned him right back around for six more years in both countries.

An American wanders into an embassy…

His initial training in diplomatic tradecraft included four weeks of general orientation and four of consular services. Just as general orientation started in July, Turkey invaded Cypress.

Metrinko, fluent in Turkish thanks to Peace Corps service, was pulled out of training and onto a task force. For two weeks he monitored an increasingly volatile situation, one which would lead to the assassination the following month of U.S. Ambassador to Cyprus, Rodger Paul Davies, and embassy secretary Antoinette Varnavas.

Returning to orientation, Metrinko asked what he’d missed.

“Oh nothing. Not interesting. Boring.”

He made his way to his first diplomatic assignment in Turkey, having mailed letters to all his friends in Ankara. He picked up his ticket and flew in on a Friday, checked into a hotel, and spent the weekend partying with his old pals.

Monday morning, he walked to the embassy and announced, “I’m here.”

“Who are you?”

“I’m supposed to start working here.”

“Yeah but, who are you?”

Metrinko had missed the part of orientation where the Foreign Service tells new officers to send a cable and letter of introduction to the ambassador. He’d missed learning about the other cable to the management counselor describing how many pets he had, the number of dependents, and the exact date of his arrival, the telegram that would spur Housing to prepare a residence, Motor pool to send a car, and Travel to have an expeditor troubleshoot any funny business at customs.

“How did you get through customs?” the astonished management officer asked.

“I walked through customs.”

“Well, What… How… Where are you staying?”

Metrinko named the hotel.

“But how did you get to the hotel?”

Everyone seemed amazed at this man appearing out of nowhere, ready to start his job in a new country one fine Monday morning. Metrinko, likewise, was stunned by their astonishment. He thought back to his first night in Turkey, a fresh Peace Corps recruit visiting the Black Sea, a singular adventure that showed him everything he needed to know about working overseas.

After a successful tour in Ankara, a brief stint in Damascus, he found himself in Tabriz, Iran.

Continuing tomorrow.

Read more from Metrinko’s oral history with the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training:

To follow Metrinko’s and other diplomats’ stories from the forthcoming Profiles in Service, consider subscribing below. And please share your thoughts in the comments section. Thank you.

##

Leave a comment