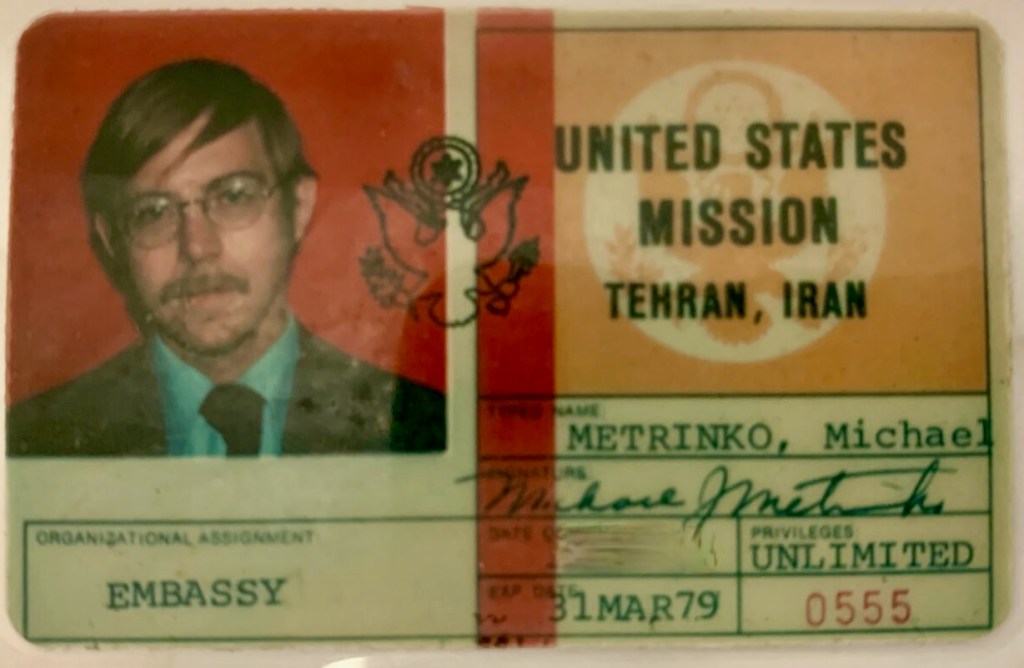

The third of three sketches translating the Peace Corps experience into crisis survival in Tehran, 1979-1981. Michael Metrinko’s full profile is scheduled for publication in Profiles in Service in 2026. Previous sketches include Victor Tomseth, John Limbert, and Sketch I of Metrinko

Tabriz

On Valentine’s Day, 1979, demonstrators stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. Four hundred miles northwest, gunfire broke out in the streets of Tabriz. There Metrinko hunkered down inside the U.S. Consulate, sheltering eight other Westerners.

Men in Air Force uniforms, armed with Uzi-like G-3s, took out all the windows and pressed their attack on the building. Metrinko reached for his phone, dialed the home of a well-connected friend, bullets zipping past his fingertips. His friend’s mother answered and Metrinko explained his predicament.

The uniformed men hauled Metrinko and the eight Westerners off to prison. They spent the day watching people dragged to trial by kangaroo court and taken outside to be hanged. Metrinko’s friend showed up, got them out, and a few days later a cargo plane brought them up to Tehran.

Propaganda sabotage

Nine months later, November 4, two long-standing contacts called Metrinko with an urgent request. They wanted to meet him before departing for Lebanon where they had a meeting with PLO leadership, including Yassar Arafat.

Knowing Metrinko kept very late nights and started his days late, they urged him to accommodate them with an early appointment. If not for them, Metrinko would have been home brewing coffee rather than entering the embassy compound moments before the students came over the gate.

The betrayal stung.

Hurt, angry, brooding, Metrinko lashed out at his captors. He was therefore treated worse than perhaps any other hostage. At all times isolated, alternately starved, stripped, frozen, and beaten, Metrinko took sadistic pleasure in tormenting the extremists. His unbridled anger and impassioned bitterness drove a vicious cycle of invective from Metrinko and seething retribution from the militant SFIL.

The day Tehran’s Friday prayer leader Ali Khamenei met with the hostages, Metrinko was cleaned up and brought to meet the cleric. Also in the room were a camera crew and the spokesperson for the SFIL, Niloufar Ebtekar.*

Ebtekar, nicknamed “Mary,” was uniformly reviled by the hostages and vilified in the West, not least as the face of Iran’s anti-Americanism delivered with precise American-accented English. A traitor of sorts, she’d lived in the U.S. for six years while her father earned a PhD at UPenn. Hadn’t America been a source of opportunity for her?

Limbert: Don’t talk nonsense, Ms. Ebtekar. You were looking for a husband, and you found one among your fellow occupiers.

His captors warned Metrinko that if he said anything wrong to Khamenei, he’d be punished. Metrinko ignored them, spoke crudely, insultingly, disrespectfully. If the camera was rolling, Metrinko determined, he’d render the footage useless as propaganda. He sought to score points against the militants, especially Ebtekar, and felt satisfaction as his minders grew increasingly uneasy.

Khamenei asked if Metrinko had any questions.

“I do have a question. I understand that one main reason for the revolution is all the poverty in Iran, the division between rich and poor, that people have no food, no money, no homes.”

“Yes,” Khamenei said, “absolutely true. We even had families sleeping on the street because they had no roof, no place to go to sleep.”

“If that’s true,” Metrinko said, pointing at Ebtekar, gold bracelets up to her elbows, “why is she wearing so many bracelets?”

Ebtekar tried covering her arms, everyone watching, the camera on her. Metrinko laughed a dark laugh, if only to himself. He knew she’d have to give up the bracelets for charity. Knowing, also, that while he could not suffer fools, he would suffer deeply for his act of defiance.

Sargent Shriver

A decade later Peace Corps founding director Sargent Shriver sought Metrinko’s advice on how to engage with Iran on participating in the Special Olympics. Metrinko would hold no grudges.

“Go to Iran if you want. And if you do, tell your son-in-law to give you three dozen autographed photos and a stack of books about him.”

“You mean Schwarzenegger? Why?”

“He’s a huge a hero there. His picture’s in every gym in the Middle East. He’s a foreigner who went to America and made it big. He’s worshipped all over that part of the world.”

Two months later, Shriver asked Metrinko to lunch again.

“I went to Iran. I wanted to tell you about my visit. You were right! All they wanted to talk about was my son-in-law. Anyway, they have so many good athletes over there, many badly injured in the Iran-Iraq war. So they have a lot of people who would be interested in competing.”

Metrinko said, “That’s a good outcome.”

“I think so, too.”

Metrinko believed what he said. He thought it a very good outcome. Less than a decade after his 444-day captivity, he harbored no bitterness toward Iran. In fact, he felt much love for the place. He still had people there he called friends, friends he would like to visit one day.

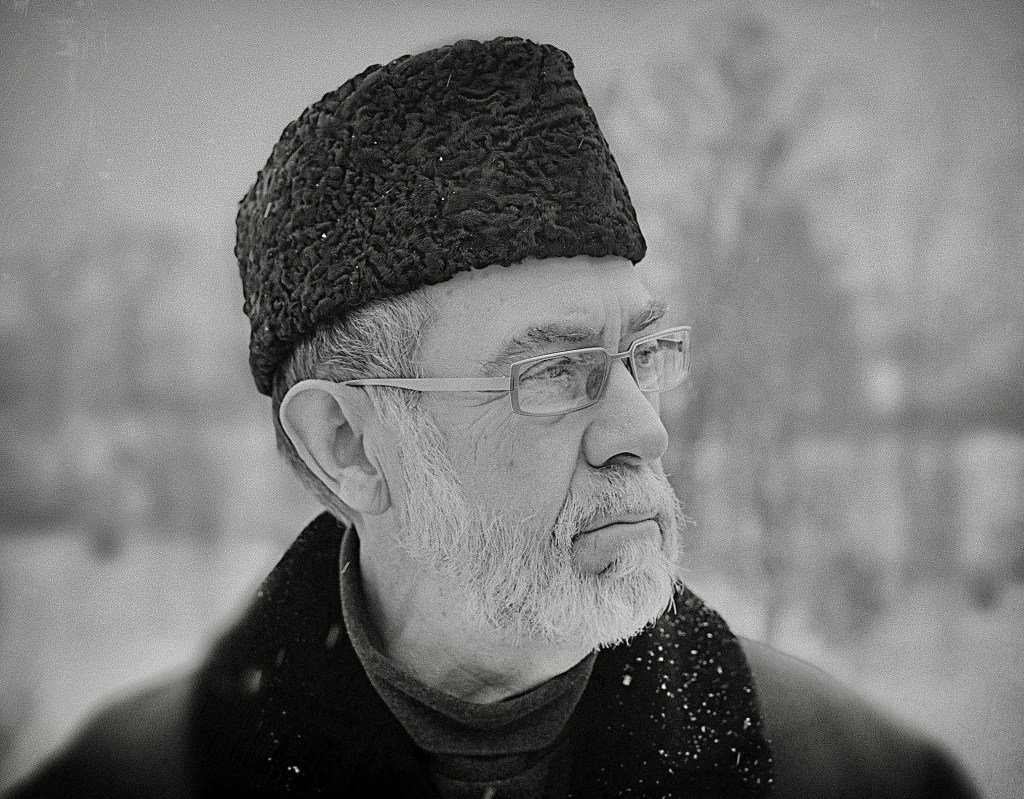

Metrinko at his home in Pennsylvania and outside his tent as a diplomat in Iraq

Read more from Metrinko’s oral history with the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training:

To follow Metrinko’s and other diplomats’ stories from the forthcoming Profiles in Service, consider subscribing below. And please share your thoughts in the comments section. Thank you.

* Ebtekar would go on to serve as Vice President of Iran, 2017-2021.

Leave a comment