Brenda Brown Schoonover, like fellow Philippines I volunteer Parker Borg, shares prolific and compelling reflections on what public service meant to her. This snapshot attempts to capture the essence. Further reading from original source material can be found at the bottom. The full profile is scheduled for publication in 2026 in Profiles in Service.

Twelve hours after completing the Peace Corps’ entrance exam on June 5, 1961, Brenda Brown received a telegram inviting her to join a group training to serve as teachers in the Philippines. In July she reported to Penn State—one of three African Americans among 168 trainees. A selection-out process eventually whittled their numbers to 128, the largest Peace Corps cohort at the time.

Brown experienced an immersion in total contrast to what she’d found in high school, where she was one of nine African Americans to integrate a Catonsville public school. “Once I joined the Peace Corps, I felt part of a team whose players had a shared purpose and like values. We became a very special family.”

During these weeks they heard from Philippines scholar George Guthrie on the country’s history, geography, and culture. Almost all cultures, Guthrie said, have the same set of values. But you have to be astute about the priority order of those values. In Eastern cultures, shame is a high priority. Guilt, on the other hand, is high in U.S. culture. Both are used to enforce self-discipline and moral order.

“Sometimes,” Guthrie said, “people in the Philippines will do things to avoid shame. And to avoid shame, they may not tell you what they really think. And that’s where you get into trouble.”

In October the volunteers touched down in a wet, muggy Manila. All wrestled with the emotions and disorientation of culture shock, a feeling that was mental as well as physical. Brown felt she adjusted more easily to being a foreigner than some of her colleagues, especially those who hadn’t experienced life under the cruel microscope of “otherness” as she had.

My response to being one of a handful of African Americans among an overwhelming majority of white students in Catonsville High turned out to be excellent training for living abroad. Instead of being intimidated because I was different, I chose to hold my head high and to wear my uniqueness with pride and as a badge of honor.

An eleven-hour train ride in December carried her to the Bicol Province, where Brown and three housemates boarded a WWII-era American Jeep converted into jeepney for the short ride to Magarao. There she was assigned to teach at an elementary school, and with a housemate developed a passion project: they hoped to establish a community library.

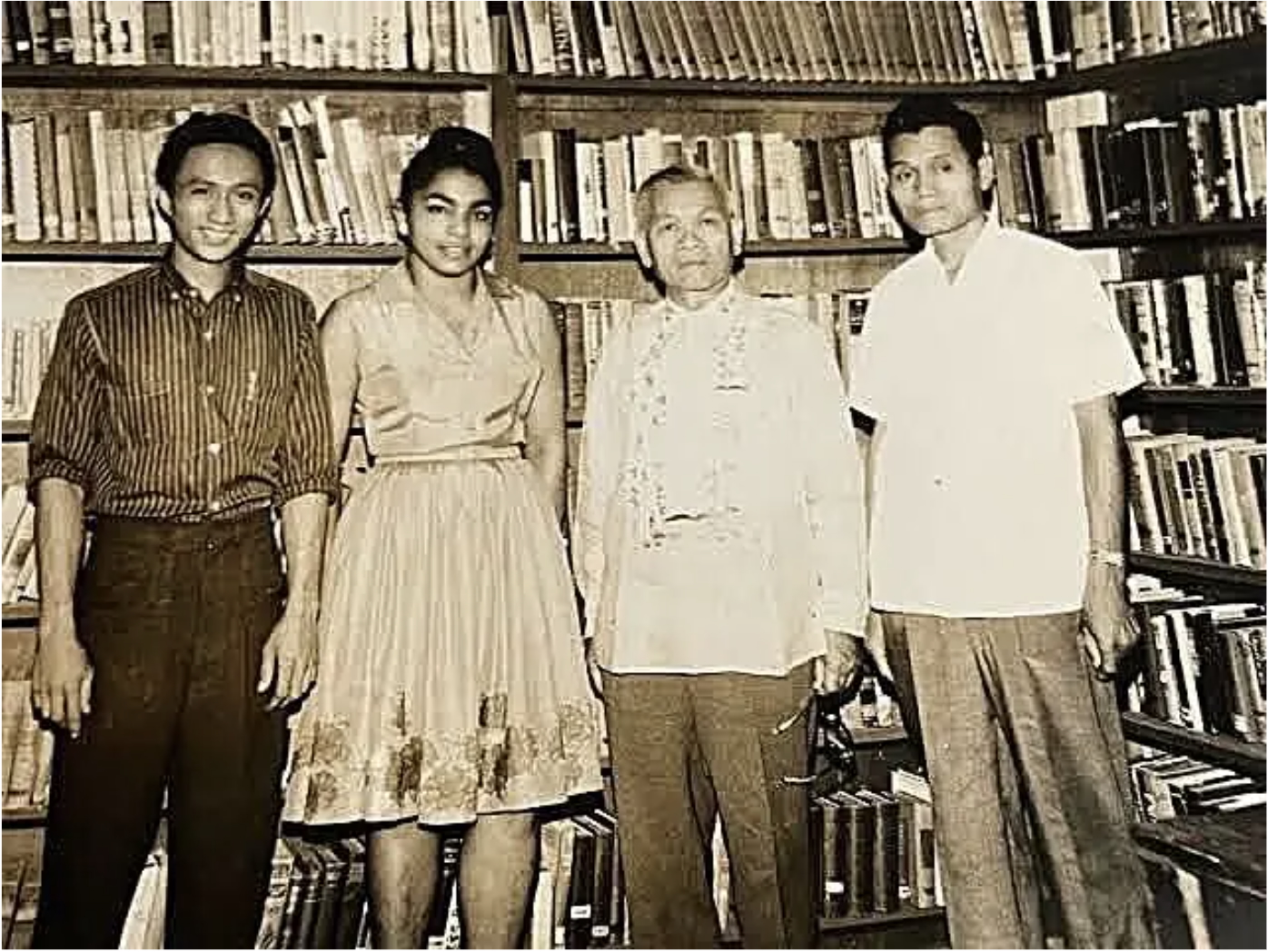

To this end she set up a taskforce and held meetings, doling out assignments to community members. She needed a proper space, a knowledgeable person to manage the facility, and lots of materials. Brown led the charge in building up a collection, writing letters to amass over 6,000 books. In time, the books began to arrive, mostly in big, heavy boxes that piled up in one room of the town hall.

As the months passed, however, she began to ask, Where are the shelves? Where are the tables and chairs? Where is the building the municipal leaders agreed to provide? Didn’t they realize a library was much more than boxes of books?

Hadn’t the townspeople agreed to this project?!

At a hastily called meeting, the volunteers shared their outrage. Brown felt deceived and embarrassed. Here she’d done all this work, coordinated the effort of so many others, rallying the generosity of people far away to build a library. For what!?

To Brown’s surprise, a male teacher stood and responded in kind, letting fly his resentment of these young American women telling him what to do.

Shocking!

Filipinos always maintained a graceful façade. From the beginning, she and the volunteers had been on a pedestal, deference Brown accepted warily—the authority she’d been granted far exceeded what she would enjoy at home. On one hand, the respect filled her with confidence. On the other, it weighed heavily.

Faced with this man’s anger, Brown thought back to what she’d learned about shame during training. She recalled handing out assignments during task force meetings, the townspeople nodding and agreeing. She’d assumed community buy-in and commitment. On reflection, what she’d seen was closer to utang na loob: smooth relationships. Saving face was supremely important.

In their gentle manner, the townspeople had gone along with the program but didn’t own it. It was just another good idea that would resolve itself…or fade away. As the town leaders saw it, they had done what was appropriate: they’d been polite. As Brown saw it, they had reneged. Now she feared she’d abused her position by publicly shaming a few honest people.

In fact, it was she who’d misread their culture.

Time cooled things off, and community members—ever gentle, wise, ready to share their experience—took on the problem. They knew Brown had acted in their interest. The town provided space for the books and assigned an attendant, the town hall janitor, who proved to be overqualified.

The experience gave much more to Brown than the joy of seeing the library completed. It taught her to explore more deeply with the people she engaged, seek straightforward and sincere responses. She learned to look beyond her pride, her own “bright ideas,” to factor in hints of reluctance and other subtle clues. She learned to be a successful communicator by being a listener.

This skill would serve her well as a Foreign Service Officer, including as U.S. Ambassador to Togo (1998-2000). There Brown Schoonover dealt directly with Africa’s strongman President Gnassingbé Eyadéma, a military general who’d come to power through a coup three decades earlier. She balanced an official push for political and human rights reforms with the need for productive relations with a central figure in resolving the civil war in nearby Sierra Leone.

The Eyadéma government also proved essential in dealing with increased security concerns following the 1998 bombing of U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

A Togolese friend suggested one potential sign of her success and influence. “Women in the rural areas are dying their hair white,” the friend observed. “Like your hair.”

“I did not know that.”

“They all say you have special power. Even over the president.”

“Well, if that’s so, I wish I knew how to use it.”

What significant moment in Peace Corps service helped change the way you engage with the world? Comment below!

##

Read more about Brenda Brown Schoonover:

Personal reflection in Answering Kennedy’s Call.

JFK Library oral history transcript.

StoryCorps interview audio.

Leave a reply to pilchbo Cancel reply